This think piece sets out findings from recent research and visits to Southern India by the Urbanism Environment Design (URBED) Trust to suggest how medium-sized Indian cities – those with populations currently of around half a million people – might cope with the pressures of future growth. It proposes five simple steps drawn from experience in promoting ‘new garden cities’ in the United Kingdom. It then describes how an experimental project to build some demonstration ‘eco-villages’ can offer solutions that could be scaled up. The conclusions identify practical ways in which collaboration between experts in the UK and those in India could be supported.

Challenges for sustainable growth

With a population of over 1.2 billion and one of the highest growth rates in the world (the GNP per head is currently increasing at 7% per annum) Indian cities are undergoing a resurgence. The largest cities, like Chennai, capital of the South Western state of Tamil Nadu, are growing fastest. Only 30% of the population are urbanised, and there is a natural tendency of those leaving their villages to seek opportunities in the biggest cities. This raises at least four challenges if cities are not to erupt in conflict:

Transport - As cities expand and sprawl, congestion and pollution becomes intolerable. Half of the 20 most polluted cities in the world are in India, led by New Delhi. The so-called ‘garden city’ of Bangalore is losing its appeal as a base for IT companies, and a powerful account of how people’s lives are changing in Tamil Nadu highlights the impact of the process of transition.[1] As Kapur (2012) points out, on the edge of Chennai ‘The farmland has become a fertile terrain for steel-framed and glass office buildings .. an urban sprawl of gated communities and plotted-out fields.’

Buses are over-loaded and have a poor image. Railways outside the mega cities concentrate on long-distance travellers, with long 20 coach trains trundling across the country from city to city. Tuc Tucs do their best, but most people manage by piling onto motor bikes or scooters. Though electric rickshaws are being trialled, dirty fuels and noise vehicles predominate. Walking and cycling are in danger of being squeezed out, and pavements are rare and poorly lit at night. As those who can buy cars and move further out, the situation could only get worse.

Housing - Stopping urban sprawl is difficult where planning powers are weak, and so much money can be made from development. High rise towers may suit people in mega cities, but a different model is needed for medium-sized cities. Detached houses on former paddy fields can only house the relatively wealthy. Unfortunately as housing becomes ever more unaffordable, as in UK cities, over-crowding worsens, and slums or ‘informal settlements’ take over land that is not being used, and that lacks services. Where plans for sustainable urban extensions have been drawn up, as in the historic French town of Puducherry (formerly Pondicherry), there are problems with implementation. Conflicts over inheritance lead to old buildings being sacrificed, and India’s heritage is disappearing before one’s eyes.

Though there are some ‘model’ alternatives, like the visionary settlement of Auroville, designed to attract people from all over the world, or the inspired low cost buildings of Laurie Baker in Trivandrum, the capital of neighbouring Kerala, they have not scaled up. Furthermore, flats built with garages and air-conditioning cost far more than most can ever contemplate. Alternatives, like the ‘custom built’ housing so popular in the Netherlands and others parts of Northern Europe, are not to be found because serviced plots are unavailable. If housing is ever to be built on the scale required, as the UN Habitat conference in Quito called for, then a more affordable and sustainable models are required.[2] This forms the basis for the URBED/SCAD (Social Change and Development) Eco House project of which more below.

Public health - Despite advances in life expectancy, infant mortality levels are still quite unacceptable. Problems arise from poorly ventilated kitchens. Many children are still under-nourished at a formative age, and families need a small plot for growing vegetables or chickens. Space to prepare nutritious food is vital, along with being able to socialise with neighbours. Walkable streets with rows of houses along them can make people feel better and safer, especially if they are lined with trees to keep the sun away, and attract birds. Children need places to play, while older people like places where they can sit together and talk.

Failing monsoons have created widespread water shortages. Large ‘tanks’ are dry and bore holes bring up saline water. While the long-term answers may lie in ‘blue green infrastructure’, as a report on applying ‘Smart City’ principles to two Southern cities points out, this calls for new approaches on the part of funders, along with some short-term projects that can demonstrate early results.[3] To a visitor, the obvious places to start are dealing with rubbish and old buildings. Piles of uncollected plastic bottles look unsightly. Yet Emirates Airlines say their blankets are now woven from thread from recycled plastic. Though monuments and temples are generally well-cared for, the public realm is generally neglected, and made worse by crumbling buildings. So there are huge opportunities for a general ‘wash and brush up’, using greenery and colour to show that places have a future and not just a past.

Community engagement - With very limited municipal resources and national programmes failing to get through to where they are needed, what can make most difference? It is possible that some of the approaches that have worked well in the UK (and European cities) might also apply to some parts of India. First comes involving neighbours and property owners in improving their streets or blocks. Premier Modi’s programme for 100 Smart Cities has apparently got lots of people talking about cities, and what they want to see. The problem of course lies in implementation. Not for profit organisations such as the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) have produced visible results in the French Quarter of Puducherry (formerly Pondicherry), while the Social and Development Group (SCAD), based in Tirunelveli, has worked with some 600 villages and 2.500 women’s groups to tackle common problems. Primary schools can provide an excellent focus for action.

Students at SCAD who competed for one of the URBED Awards certainly seemed very proud of their city, its history and current attractions. It would seem an easy step to go from research into publicity, making the most of the internet and phone apps. But this requires educational bodies to introduce practical projects as part of the curriculum, and for communities to recognise effort and achievement. This is where we hope our SURGe web site can help in sharing good practice.

From vision to reality

Describing what is wrong or where one would like to be is usually far easier than finding a route for getting there! But our experience over the last 40 years is that progress needs to be made through balanced increment development with flexible plans but clear measures of success that win general support. We want to promote and test out a ‘route to smarter urbanisation’, that is one where more people lead full lives, which requires development and infrastructure to be in balance. Drawing on experience in the English university city of Cambridgeshire and surrounding County, we argue that there are five critical steps:

- Collaboration - Successful growth and ‘smart cities’ depend on generating innovation and good jobs. The best examples of transformation in Europe have all involved municipal authorities playing proactive roles, and creating the right climate for long-term investment.[4] But what can you do where local authorities are apathetic or under-resourced? Here examples such as Leipzig in the former Soviet part of Germany or Eindhoven in the Netherlands, who lost its major employer and had to reinvent itself, offer models. The key is showing the outside world that the key ‘stakeholders’, which include universities and major employers, have a ‘shared vision’ for where they want the city to go. The best models involve ‘polycentric cities’ that make the most of their existing assets, and that use development to overcome barriers to growth.

- Connectivity - The motor car, which was a major driver of city growth in after the Second World War, is now recognised to be a dangerous weapon in the wrong hands! So cities that once demolished buildings to create urban freeways, are now taking steps to ‘tame the car’, and give priority on the ground to pedestrians and cyclists. Indian cities such as Madurai have also shown the value of overruling local interests, such as small shops, in order to raise income levels generally through better urban quality. While only some, like Chennai and Kochi, may be able to justify new overhead or underground Metros, many more can benefit from Integrated Public Transit, and from managed parking. The railway lines that branch out from junctions such as Tirunelveli offers huge untapped potential for creating a 21st century networked city with denser development around stations. So too is the scope for tapping solar power for recharging electric bikes.

- Community - Though there can be deep-rooted differences between caste and class, as well as religion, there is also great value as SCAD is showing through its schools and colleges, in bridging the gulfs. Indeed some of the best places to live are where there is a diversity of people, especially in terms of age and wealth. Writers like Akash Kapur and Amartya Sen highlight how the old distinctions are breaking down in modern India, thanks to universal education and enlightened laws. However the relatively slow rate of growth of Auroville also brings out the problems that can arise when the differences are too great. So new settlements need to appeal to groups that have something in common and that share similar values if they are to flourish.

- Climate-proofing - The challenges of tackling water shortages and periodic flooding, along with energy failures and the need to reduce carbon emissions, tend to lead to plans for mega projects that can take decades to implement. But there are also a range of small-scale projects that can make a visible difference. Thus students in Tuticorin called for schools to promote the value of saving water, and for water companies to distinguish between different qualities of water. Innovative eco technologies such as composting toilets, the use of 12volt local energy grids, and harvesting industrial hemp (which uses a sixth of the water of cotton, enriches the soil, and removes carbon dioxide from the air) can be combined to produce a better life and living for those living in rural areas.

- Character - New developments are often criticised for all looking the same, and much of the identity of traditional communities is being lost as cities grow and redevelop old areas and buildings. This has led in the West to initiatives to promote conservation and adaptive reuse. In the USA the idea of ‘smart growth’ is supporting cities that develop around ‘Transit Oriented Development’, with a mix of uses to cut travel times. In turn this can result in much more attractive looking places, where households can put their efforts into creating somewhere special. However possibly the most important measure of all lies in using ‘blue and green infrastructure’ to enhance fine buildings and places, and bring the best of the country into the town.

Eco-village projects as a way forward?

The SCAD ‘eco-villages’ project forms a building block in an ambitious proposal to test out the application of ‘garden city’ principles to the growth of the City of Tirunelveli and nearby cities such as Tuticorin, and to develop the skills and job opportunities for staff and students at SCAD (Social Change and Development) The local authority is competing to become designated in the government’s Smart City programme, and hopes to build an exemplary new settlement on the edge as well as to take traffic out of the historic centre. If the city were to double in size by 2050, assuming a growth rate of 2% a year, there is a danger of land being taken away from productive agriculture, and congestion on the roads could become socially and environmentally intolerable. It is therefore vital to have a strategic growth plan that incorporates the surrounding suburbs and villages, and avoids car use.

The proposals for this project are based on applying good practice in Europe, by making better use of land that would not otherwise be developed. With the help of ConnectedCities, a social enterprise based in London, we have identified potential land owned by Indian State Railways close to stations that could be suitable. This is being explored in the Tirunelveli case study. It is also important to find ways of reducing carbon emissions and pollution, by minimising the use of concrete and using natural materials instead. The new homes need to be affordable to people whose basic incomes mainly come from agriculture, and to offer better options than currently available. Above all water must be used more carefully to avoid shortages in times of drought.

We think that the principles applied in the original garden cities and new towns in the UK, and promoted by the Town and Country Planning Association, could offer a proven way forward for some mid-sized Indian cities, provided there is a suitable delivery and financing mechanism. We believe the proposals for Uxcester Garden City - our winning entry for the Wolfson Prize about garden cities - could provide some of the answers.[5]

Going back to first principles its useful to remember what the Town and Country Planning Association has set out as garden city principles:

Garden city principles (TCPA 2012) [6]

- strong vision, leadership and community engagement;

- land value capture for the benefit of the community

- community ownership of land and long-term stewardship of assets;

- mixed-tenure homes that are affordable for ordinary people;

- a strong local jobs offer in the garden city itself & within easy commuting distance;

- imaginatively designed homes with gardens in healthy, vibrant communities;

- generous green space linked to the wider natural environment, including allotments;

- strong local cultural, recreational and shopping facilities in walkable neighbourhoods; and

- integrated and accessible low-carbon transport systems.

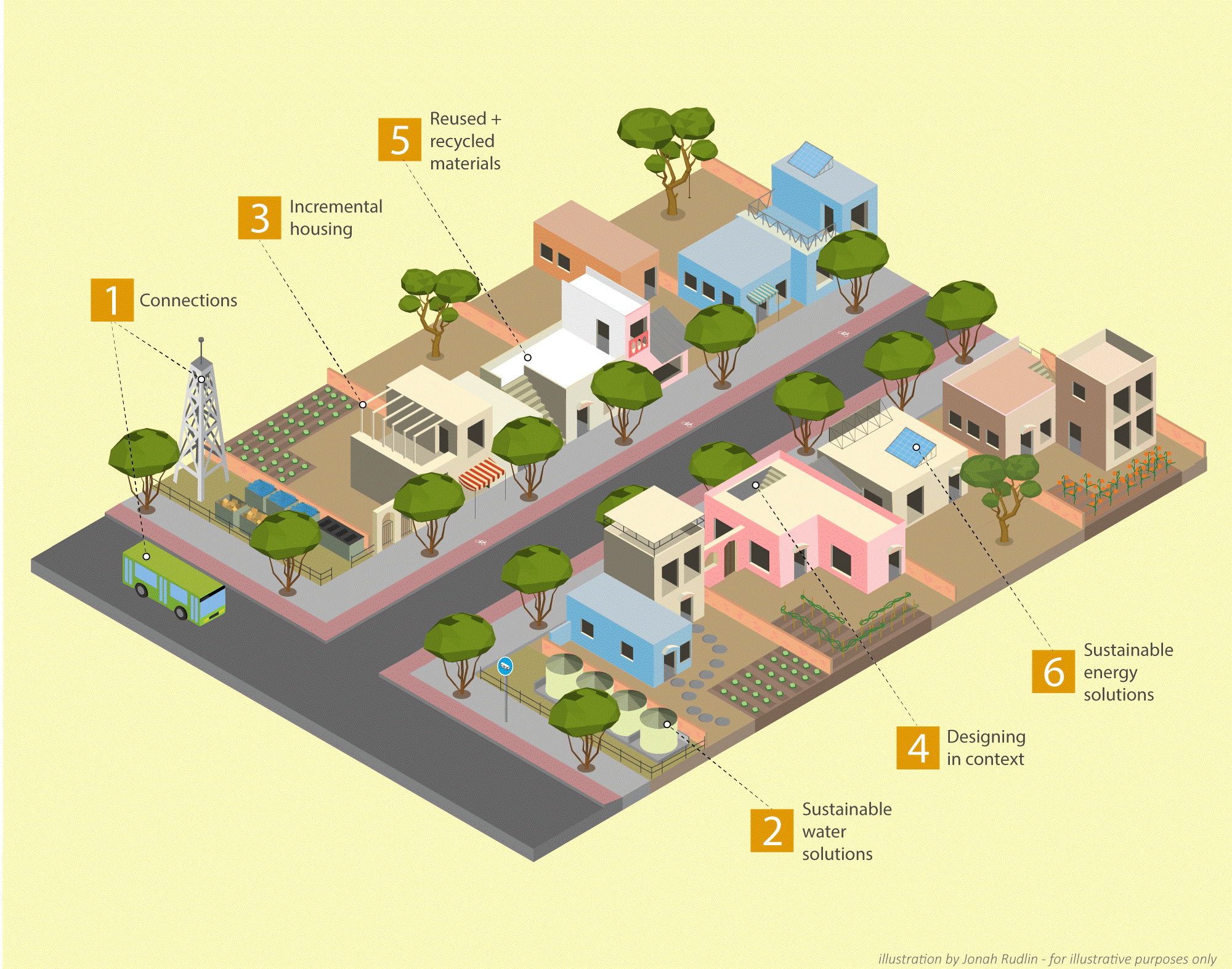

Innovative design features SCAD Eco Houses should aim to innovate in seven main ways and we have shown some of these in the illustrative drawings that accompany this think piece:

- Maximum use of public transport, walking and cycling to help improve air quality and public health through location on transport corridors or near stations as well as good Information Technology connections

- Sanitation measures to minimise unnecessary water consumption while improving health, for example through drawing water from restored local ‘tanks’ , and processing waste products

- Plots that enable subsequent extensions and improvements, including space for ‘kitchen gardens’ for healthier living, and lots of trees for natural cooling to avoid the need for air conditioning

- Designs that response to local vernacular, such as terraced streets or courtyards that support active communities, but that also provide space for contemporary needs: eg storage, toilets and waste disposal or recycling

- Construction out of reused and recycled materials, and that explore the potential for using natural materials, such as ‘rammed earth’ or Hempcrete that combines local lime with using the stems from growing industrial hemp for the clothing and motor industries. This would reduce the high carbon emissions from the use of concrete and provide farmers with a cash crop.

- Use of 12/24 volt electricity from solar panels with mini grids, and natural ventilation and insulation to reduce carbon emissions and dependence on an unreliable electricity grid

- Collaboration between sources of knowhow, land owners, and communities supported by progressive local authorities.

In short the new ‘eco homes’ will aim to minimise the consumption of scarce resources and would enable mid-sized cities such as Tirunelveli to grow without ‘costing the earth’. They will appeal to people moving out of villages into homes of their own, as well as to municipalities and utilities wanting a more sustainable alternative to urban sprawl. They can be built by small and self-builders, offering a much better alternative to crowded slums, and creating local employment. ‘Eco-villages’ will combine the capacity for traditional forms of housing to co-exist happily with the planet, while achieving the levels of aspiration associated with urban life styles and new technologies. For example mobile phone apps can be used to encourage healthier living and overcome the isolation associated with new settlements. A linked project will draw lessons and apply them in training students, for example through awards for group work in producing essays on affordable homes, natural resources or hospitality.

In summary

In our view the greatest value of the eco-village project will also come from its potential to be extended and to act as a model for other areas in line with garden city principles. The basic challenge in building sustainable homes anywhere is providing advance infrastructure, such as roads and schools, which is where the growth of certain European cities offer many lessons. As infrastructure can cost as much as building new housing, it is important to make the most of what already exists. This includes not just transport but also energy and soft infrastructure such as hospitals and colleges. It is also important to minimise water consumption and waste, and to tap solar power to make new homes independent of unreliable state power sources, and make the most of natural resources. We hope this project will help us understand more about how to take this forward.

[1] Akash Kapur, India Becoming: a journey through a changing landscape, Penguin Books, 2012

[2] Laura Petrella et al, Planned City Extensions: analysis for historical examples, UN Habitat, 2015

[3] Atkins with UCL, Future Proofing Indian Cities: key findings from applying a future proofing approach to Bangalore and Madurai, March 2015

[4] Peter Hall with Nicholas Falk, Good Cities Better Lives: how Europe discovered the lost art of urbanism, Routledge 2013

[5] Nicholas Falk and David Rudlin, Uxcester Garden City, URBED 2014 www.urbed.coop

[6] Town and Country Planning Association Creating Garden Cities and Suburbs Today, TCPA 2012